Diverse faculty attracts diverse students

February 03, 2022

Having diversity in the front of the classroom benefits all students, especially the students of color who may not be used to seeing people like themselves in that position, said Mark Dawkins, CPA, Ph.D., professor of accounting at the University of North Florida and the first Black CPA, Ph.D., president-elect of the American Accounting Association.

Among other things, the person teaching the class can have a significant impact on whether students decide to try a course in that subject — and ultimately make it a career — because they see it is being taught by someone who likely embodies similar life experiences. For that reason, the first Black CPA Ph.D.s, and the professors they mentored or inspired, have played an important role in attracting generations of ambitious Black students to the profession.

Overcoming barriers

The earliest Black people to earn Ph.D.s in accounting faced numerous barriers. In fact, the first five “had no chance at full-time positions in majority-white institutions” when they got their start in the 1950s and 1960s, according to Theresa A. Hammond, Ph.D., accounting professor at San Francisco State University’s Lam Family College of Business and author of A White-Collar Profession: African American Certified Public Accountants Since 1921.

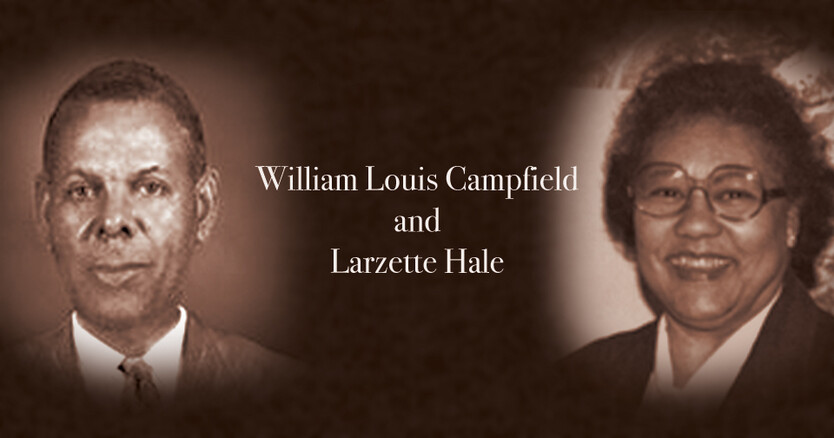

That was the case for William Louis Campfield (1912–1993), who in 1951 became the first Black CPA Ph.D. He was also the first Black CPA in North Carolina and the first Black person inducted into the Beta Alpha Psi organization. His parents, graduates of the Tuskegee Institute and students of Booker T. Washington, were teachers, according to research by Dereck Barr-Pulliam, CPA, Ph.D., assistant professor of accountancy at the University of Louisville. Campfield and his eight siblings attended a school on the Institute’s campus and then he was sent to live with relatives in Pittsburgh so he could attend a college preparatory high school. He enrolled in New York University, supporting himself by working at a bowling alley, then returned to teach at Tuskegee in 1933.

When it hired Campfield in 1951, the University of San Francisco had the distinction of being the first majority-white institution in the country to hire a Black Ph.D. in accounting, according to Hammond. However, he was hired as a lecturer, not a professor, even though no other faculty member, including the dean, had a Ph.D. A year later, Campfield returned to working in accounting in a government position and created a practitioner-in-residence program that allowed him and numerous other government accountants to take leave and teach accounting. He retired in 1972 as associate director of what was then called the U.S. General Accounting Office, now known as the Government Accountability Office, and in 2019 became the first Black accountant to be inducted (posthumously) into the American Accounting Association’s Hall of Fame.

Succeeding through persistence

Another pioneer, Larzette Hale (1920–2015), showed similar determination. Sent to an orphanage at age 11 after her father’s death and when her mother could no longer care for her, she learned bookkeeping when the business office’s accountant took an interest in her. She went on to study business in college, where an accounting professor became her mentor. “Thanks to her, I fell in love with balancing the books and knew I wanted to study accounting in college,” Hale told the Journal of Accountancy in 2009.

She faced a number of forms of discrimination. Although a resident of Oklahoma, Hale was barred from attending its two state universities because of her race, so she attended Langston University, the state’s only historically Black college. The state of Oklahoma would later pay her tuition to attend the University of Wisconsin for her master’s degree, according to Hammond. While teaching at Clark College in Atlanta, she decided to get her CPA at the urging of her mentor, Jesse Blayton, an influential early Black accounting professor. When Hale took the CPA exam, she was asked to sit in the back of the room and wasn’t allowed to use the lunchroom. In 1955, she became the nation’s first female Black CPA Ph.D. She ran a solo practice for a decade but was drawn to teaching. Hale would ultimately become the head of Utah State University’s school of accountancy and also taught at Langston and Brigham Young. She was appointed a regent of the Utah Board of Higher Education, the first Black person in that role.

A first for a new generation

Dawkins, who met Hale early in his career, set out to follow the lead of these early pioneers. “There are a lot of prominent and impactful faculty of color who may not have had an opportunity to serve in this role, so I stand on the shoulders of giants,” he said. He said he’s grateful for the chance to highlight issues and concerns related to diversity at a time when attention is being focused on racial injustice and economic inequity.

Dawkins promotes the advancement of future Black accountants through his involvement in the PhD Project, which aims to diversify corporate America by increasing the number of business professors from underrepresented minority communities and attract more minority students to college business courses. He was in graduate school before the PhD Project started, but he began attending the project’s annual conference as soon as it began. Currently, he co-mentors four junior faculty members involved in the project, discussing questions they may have about research or teaching and helping them build the success they need to gain tenure. When the project began, Dawkins recalled that there were so few faculty of color that they would refer to each other by number based on the order in which they had become Ph.D.s. “Today, we have 1,500,” he said.

Expanding students’ knowledge base

To keep the momentum going, efforts are underway to nurture a new generation of diverse CPA Ph.D.s and provide them with the learning and tools they need to succeed. For example, Dawkins served on a task force for CPA Evolution, a joint initiative of the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy and the AICPA to transform the CPA licensure model to encompass the rapidly changing skills and competencies that accountants need now and in the future. That will include changing what is being taught. “I believe accounting schools do a good job of giving students the basic toolkit they need,” he said. “But we will need a combination of schools better preparing students and firms enhancing employee training.” Speaking of his work with the learning process and the PhD Project, Dawkins concluded, “for me, it’s a lifelong commitment.”

The Black CPA Centennial was a yearlong effort to honor, celebrate, and build upon the progress Black CPAs have made in shaping the accounting profession. The celebration is a collaborative effort of the AICPA, Diverse Organization of Firms, Illinois CPA Society, National Association of Black Accountants, and National Society of Black CPAs. This article was originally published by the Illinois CPA Society.